Introduction: Why Global Governance Matters in the Blue Economy

The Blue Economy—defined as the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and ocean ecosystem health—has become a central pillar in international development discourse. But its promise can only be realized through robust, coordinated global policy and governance frameworks. These frameworks shape not just economic models but also influence spatial planning, coastal infrastructure, cultural identity, and climate resilience.

This article explores how global ocean governance—anchored in UN Sustainable Development Goal 14, the UN Decade of Ocean Science, and the EU Blue Economy framework—intersects with design, planning, and landscape architecture to create regenerative and inclusive futures for our oceans and coasts.

1. UN Sustainable Development Goal 14: Life Below Water

Goal 14: "Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development" is the UN’s most direct call to action for the Blue Economy. This goal directly addresses critical issues such as overfishing, marine pollution, ocean acidification, and habitat destruction. It includes targets to:

-

Reduce marine pollution.

-

Protect marine ecosystems.

-

Regulate fishing.

-

End harmful subsidies.

-

Increase scientific knowledge.

Current Situation

Despite progress, the UN’s 2024 Ocean Report warns that:

-

35% of fish stocks are overexploited.

-

Coastal ecosystems like mangroves and seagrasses continue to shrink.

-

Marine plastic pollution is increasing, not decreasing.

Despite its urgency, SDG 14 is often described as one of the most underfunded and overlooked of the SDGs.

Role of Design and Landscape Architecture

While much of SDG 14 focuses on governance and science, design disciplines can accelerate its implementation:

-

Urban waterfront revitalization (e.g., Rotterdam, Sydney) helps restore habitats while improving public access.

-

Marine parks and seascape corridors, designed with aesthetic and cultural sensitivity, support biodiversity and tourism.

-

Floating and amphibious structures, pioneered by firms like Waterstudio NL, align with SDG 14.2 (sustainable marine ecosystem management).

Example: Nordhavn District, Copenhagen: A Model for Floating Urbanism and Ocean Integration

Program: Master plan for new city district in former industrial harbour area, including development plan, district plans, design of public spaces, streetscapes and promenades, landscaping, bicycle infrastructure and metro stations. (Source: cobe.dk)

Nordhavn—once a vast industrial port—is being transformed into a climate-adaptive urban waterfront aligned with the UN SDG 14: Life Below Water. Spearheaded by the Danish architecture firm Cobe, the city and port authorities have partnered with marine biologists, engineers, and urban designers to embed ocean ecology into the very DNA of the district.

Key Features:

-

Floating public spaces that rise with sea levels, ensuring long-term adaptability to climate change.

-

Seaweed farming modules developed in partnership with marine ecologists to create local bio-economy loops—turning marine biomass into food, bioplastics, and fertilizer.

-

Ecological piers and biodiverse edges that blend public access with habitat restoration (e.g., for mussels, eelgrass, and fish nurseries).

Broader Significance:

This initiative exemplifies how marine spatial planning, green-blue infrastructure, and social inclusion can coexist through careful, research-driven design. Nordhavn isn't just about economic development—it's a testbed for integrating marine life into the urban experience.

Nordhavn as it looked before the extension began in 2008 (left) and Nordhavn as it will look when fully expanded (right). (Source: cobe.dk)

2. UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021–2030)

The UN Decade aims to mobilize global science, technology, policy, and communities to support a sustainable ocean economy. Its mission: “The science we need for the ocean we want”, with a particular focus on seven outcomes, including clean oceans, resilient ecosystems, sustainable fisheries, and equitable ocean access.

Current Situation

The Decade emphasizes:

-

Co-design of solutions with stakeholders (from Indigenous leaders to city planners).

-

Use of digital twins, remote sensing, and data visualization for planning.

-

Greater integration of social sciences and design into ocean science.

Yet there is often a gap between data and action, especially at the urban-coastal interface.

Role of Design and Landscape Architecture

Turning ocean science into actionable, spatial, and community-centred strategies requires more than just data. It requires design thinking, public engagement, and built interventions. Here, architects, planners, and landscape designers can translate complex ocean data into interactive public spaces, educational installations, eco-sensitive infrastructures, and marine conservation zones. The Decade offers a platform for cross-disciplinary collaboration, where designers and scientists co-create innovations—such as floating laboratories, ecological piers, and interactive seascapes—that make ocean science visible and impactful at the human scale

-

Translating data into spatial plans: Designers help interpret ocean science into zoning, visualizations, and built interventions.

-

Creating living labs: Waterfronts as real-time testbeds for monitoring, adaptation, and public engagement (e.g., Rotterdam’s Floating Pavilion).

-

Communicating ocean science: Through storytelling, exhibitions, and design installations (e.g., Studio Swine’s Sea Chair made from marine debris).

“Design is where science meets the public imagination.”

— Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, marine biologist and policy expert

3. The EU Blue Economy Framework and International Marine Agreements

The European Union has developed a comprehensive framework to support the blue economy in line with climate, biodiversity, and innovation goals.

Key Elements

-

The European Green Deal (2019): Integrates the blue economy with the circular economy, climate neutrality, and biodiversity strategies.

-

The Sustainable Blue Economy Communication (2021): Focuses on offshore energy, coastal resilience, aquaculture, tourism, and marine spatial planning (MSP).

-

Alignment with international frameworks like the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and CBD Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) treaty.

Current Situation

The EU faces both innovation and pressure:

-

Progress in offshore renewables (e.g., wind farms in the North Sea).

-

Conflict between economic use (ports, shipping, tourism) and environmental protection.

In this policy context, design and spatial planning emerge as tools of implementation—translating regulatory goals into transformative landscapes and infrastructures. Landscape architects, urban planners, and architects play a key role in designing adaptive coastal settlements, green ports, and cultural seascapes, while also integrating community needs, heritage values, and marine biodiversity. Through EU-funded initiatives like Horizon Europe, Interreg, and LIFE programs, multidisciplinary design teams are being supported to prototype scalable solutions for a thriving, just, and regenerative blue economy.

Design and Planning Opportunities

-

Eco-sensitive port development: EU-funded projects like Green Port of the Future (Ghent, Belgium) integrate green infrastructure and emissions control, often with the input of landscape architects.

-

Marine spatial planning (MSP): Coastal planners now use GIS tools and participatory design methods to balance marine use zones (fishing, energy, tourism).

-

Cultural seascape preservation: Landscape architects are increasingly involved in maintaining underwater heritage sites and traditional fishing landscapes (e.g., Mediterranean coastal villages).

Examples of Interdisciplinary Impact

1) Translating Ocean Science into Spatial Design: From Data to Urban Form

Designers and planners act as critical intermediaries who interpret complex oceanographic, ecological, and climate data into visual, spatial, and built realities.

Methods Used:

-

GIS-based marine spatial planning (MSP) to map fishing grounds, shipping lanes, protected zones, and sea level rise risks.

-

3D visualization tools and participatory maps to engage communities in reimagining waterfronts.

-

Scenario modelling (using climate and biodiversity data) to guide future urban forms—like nature-based flood barriers or amphibious housing.

Case in Point:

In New Zealand, the Auckland waterfront redesign incorporates Māori knowledge systems with hydrological modelling to create culturally respectful, resilient coastal edges. Designers worked directly with oceanographers and Indigenous groups to spatially interpret traditional reef protections.

2) Creating Living Labs on Waterfronts: Testing Sustainability in Real Time

Waterfronts are increasingly being developed as "living laboratories", where design, science, and citizen engagement converge to test adaptive solutions to climate and marine pressures.

What Makes a Living Lab?

-

Sensor-based infrastructure (monitoring water quality, tides, biodiversity).

-

Pilot projects for floating wetlands, urban aquaculture, or blue carbon sequestration.

-

Public participation hubs that promote ocean literacy and stewardship.

Example: Rotterdam’s Floating Pavilion

Designed by DeltaSync and PublicDomain Architects, this climate-adaptive structure floats in the Rijnhaven basin and demonstrates how cities can respond to rising seas. It also functions as a science communication centre, showcasing data on urban flooding and biodiversity.

Rotterdam’s Solar-Powered Floating Pavilion is an Experimental Climate-Proof Development (Source: Jason Sedar_Inhabitat.com)

3) Communicating Ocean Science Through Storytelling and Design

Beyond infrastructure, designers play a powerful narrative role in translating complex marine issues into accessible, emotionally resonant stories that inspire behavioural change.

Key Mediums:

-

Exhibitions and installations (e.g., Studio Swine’s Sea Chair made from marine plastic).

-

Augmented reality and interactive maps that visualize coral bleaching, sea level rise, or ocean currents.

-

Community workshops and artistic residencies in fishing towns or marine parks.

Example: “Territorial Agency: Oceans in Transformation”

This exhibition (commissioned by TBA21–Academy and hosted at Ocean Space in Venice) transformed satellite data, interviews, and geospatial modelling into immersive architectural drawings and films—curated with help from marine scientists and spatial designers.

4) Eco-Sensitive Port Development: Green Port of the Future, Ghent (Belgium)

The Green Port of the Future in Ghent is a leading EU project aimed at redesigning port infrastructure to meet both ecological and logistical needs.

Key Elements:

-

Green buffers and stormwater wetlands designed by landscape architects to filter runoff and provide habitat.

-

Shore power systems to reduce emissions from docked ships.

-

Circular economy loops using dredged materials and port waste for eco-construction.

Design and Planning Role:

Landscape architects and urban designers worked on softening edges and reintegrating the port into the urban green-blue network, offering public access while reducing ecological footprint. These efforts are part of the EU's TEN-T corridor greening initiative.

5) Cultural Seascape Preservation: Merging Heritage with Ecological Goals

Landscape architects are increasingly guardians of cultural seascapes—coastal and marine environments that hold ecological and heritage value.

Examples:

-

Traditional fishing villages (e.g., in Sardinia or Crete) where spatial design protects vernacular coastal architecture and supports local livelihoods.

-

Underwater heritage trails in Croatia or Turkey—co-designed with marine archaeologists—allow for eco-tourism while protecting shipwrecks and submerged ruins.

-

Community-driven mapping of sacred coastal sites (e.g., in Hawai‘i or Indonesia), integrating Indigenous spatial knowledge into conservation zones.

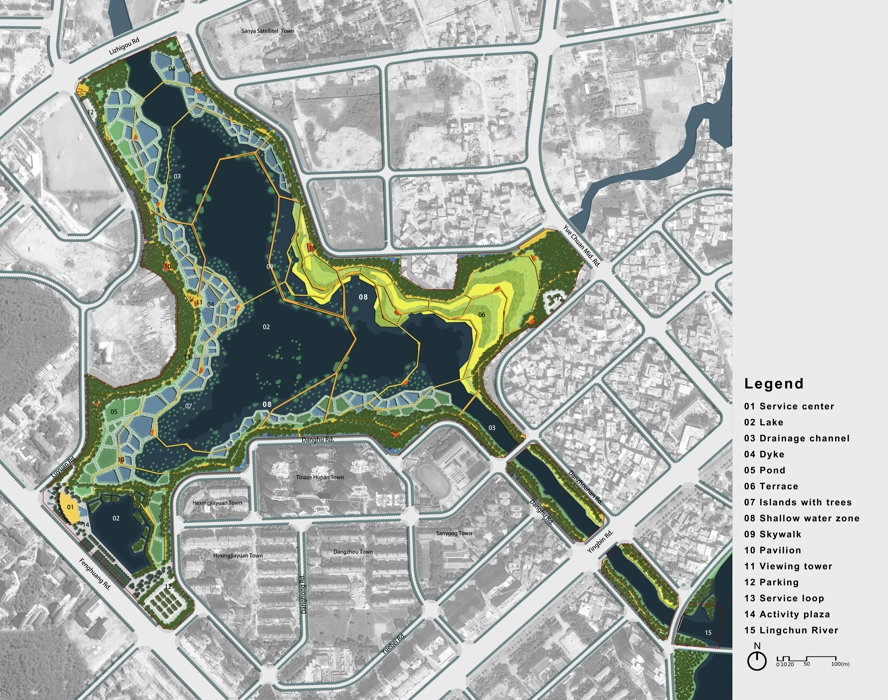

Practice Spotlight: Turenscape (China)

In projects like the Sanya Dong'an Wetland Park, Turenscape merges natural hydrology with cultural interpretation, turning flood-prone coastlines into educational landscapes that honour both ecology and local maritime traditions.

Sanya Dong'an Wetland Park (Source: turenscape.com)

Conclusion: A Call for Integrated Action

Policy and governance are indispensable to the success of the Blue Economy—but they cannot act alone. Designers, planners, and architects are key agents of transformation: they shape how global frameworks become local realities. By aligning with SDG 14, the Ocean Decade, and the EU’s sustainability mandates, design can catalyse systems thinking, spatial justice, and ecological restoration.

To succeed, the Blue Economy must not only be governed—it must be envisioned, experienced, and inhabited differently. That’s where the power of design lies.

“The ocean is not a void to be filled with industry; it’s a space of memory, meaning, and life. Governance must reflect this—so must design.”

— Professor Kristina Hill, Landscape Architect, UC Berkeley

Featured Posts

Blog Topics

Urban environment & Public spaces

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Waterfront & Coastal Resilience

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Captivating Photography

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Why Read The Landscape Lab Blog?

The way we design and interact with landscapes is more important than ever. As cities expand, coastlines shift, and climate change reshapes our world, the choices we make about land, water, and urban spaces have lasting impacts. The Landscape Lab Blog is here to spark fresh conversations, challenge conventional thinking, and inspire new approaches to sustainable and resilient design.

If you’re a landscape architect, urban planner, environmentalist, or simply someone who cares about how our surroundings shape our lives, this blog offers insights that matter. We explore the intersections between nature and the built environment, diving into real-world examples of cities adapting to rising sea levels, innovative waterfront designs, and the revival of native ecosystems. We look at how landscapes can work with nature rather than against it, ensuring long-term sustainability and biodiversity.

By reading The Landscape Lab, you'll gain a deeper understanding of the evolving field of landscape design—from rewilding initiatives to regenerative urban planning. Whether it’s uncovering the forgotten history of resilient landscapes, analyzing groundbreaking projects, or discussing the future of green infrastructure, this blog provides a space for learning, inspiration, and meaningful dialogue.

Location:

The Landscape Lab

123 Greenway Drive

Garden City

NY 12345

United Kingdom

Contact Number:

Get in Touch:

contact@thelandscapelab.co.uk

© 2025 thelandscapelab.co.uk - Your go-to blog for landscaping insights