Practical success in the blue economy comes when finance, technology, ecology, governance — and crucially design and place-making — converge. The four case studies below illustrate distinct levers: large-scale energy transition (Norway), innovative ocean finance (Seychelles), sustainable aquaculture (Portugal), and community-led nature restoration linked to tourism and livelihoods (Kenya). In each case I show the present reality, what’s being tried, and how designers, planners and landscape architects can shift outcomes toward equity, resilience and ecological restoration.

1) Norway — Offshore energy transition (focus: floating wind)

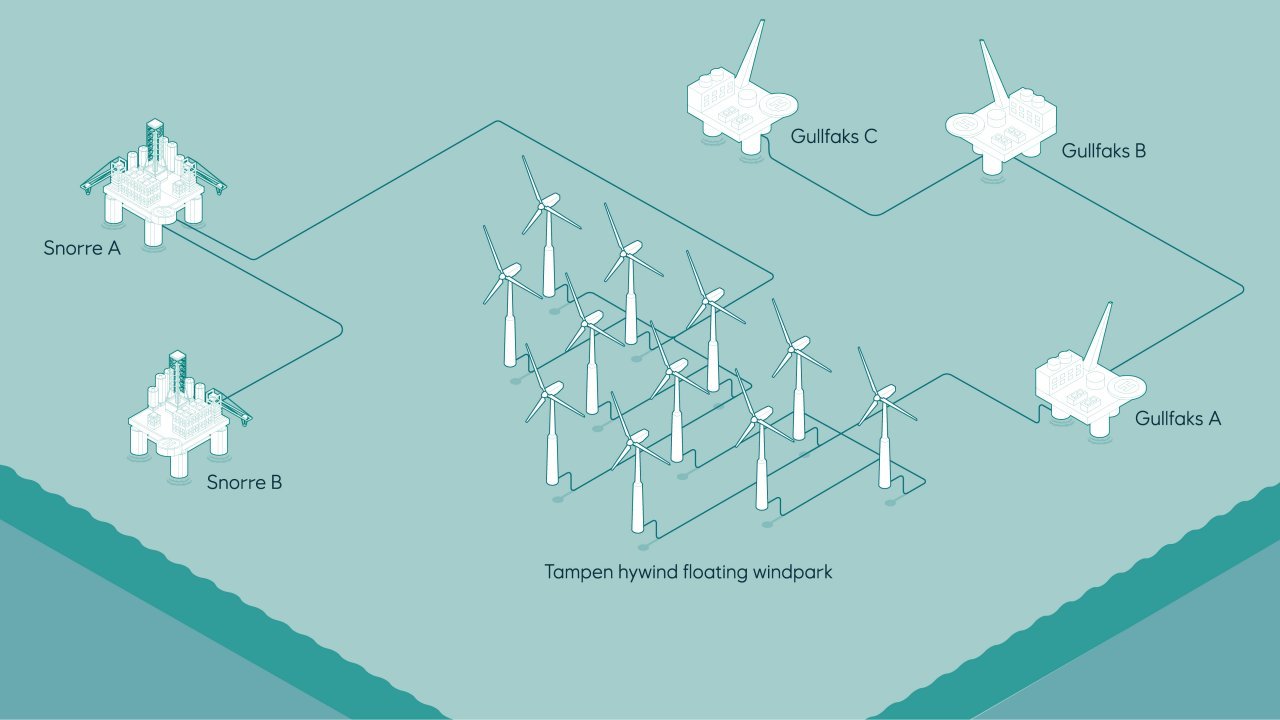

Hywind Tampen floating wind farm illustration. The world’s first large-scale floating offshore wind farm, built to power oil and gas facilities. (Source: equinor.com)

What’s happening now (overview)

Norway has moved from oil-and-gas world-leader to an active developer of offshore renewable energy — especially floating offshore wind because of its deep-water continental shelf. The country has already demonstrated floating wind at commercial scale (e.g., Hywind Tampen) and in 2024–25 launched competitive tenders for large-scale floating wind zones (Utsira Nord and Sørlige Nordsjø II) with planned subsidy frameworks to de-risk first movers. These tenders are a major step toward building a large floating-wind industry on the Norwegian shelf.

Key technical & governance challenges

-

Floating wind requires new supply chains, specialized installation and maintenance ports, export cable corridors, and consenting regimes that balance fisheries and biodiversity.

-

Public attitudes (visual impact, fishing access) and cost pressures (subsidies) shape feasibility. Recent Norway public-opinion studies and commentary show mixed local support which requires careful siting and stakeholder engagement.

How design, planning and landscape architecture change the game

Designers and landscape architects play both hard- and soft-power roles:

-

Seascape-aware siting & visual design

-

Use 3D visual simulations, view-shed analysis and “immersive visualizations” to evaluate visual impact from key coastal vantage points and tourism corridors; incorporate mitigation (lighting strategies, turbine layout patterns) into tender requirements to reduce social friction.

-

-

Port and logistics design

-

Re-purpose and retrofit port precincts into service hubs (assembly, operation & maintenance bases, crew transfer vessel berths) with low-carbon infrastructure, humane worker housing, and biodiversity buffers. Design can fold in floating assembly yards and modular quays that minimize dredging.

-

-

Integrated marine spatial planning (MSP)

-

Designers turn oceanographic, fisheries, and shipping data into stakeholder-facing maps that reveal trade-offs and options — enabling co-designed corridors that minimize conflicts between wind, fisheries, and shipping lanes. These visual outputs make MSP actionable during permitting.

-

-

Ecosystem-sensitive foundations and subsea design

-

At a technical level, engineers and designers can shape anchoring systems and subsea objects to encourage epibenthic communities (reefing effects) while minimizing seabed disturbance; architects design turbine platforms and O&M bases with low visual and ecological footprints.

-

Example design outcomes to replicate

-

Siting workshops that pair 3D visualizations with fisher interviews to produce conditional concession maps.

-

Blue-port design briefs requiring low-emissions shore power, stormwater wetlands to filter run-off, and publicly accessible educational piers that explain offshore renewables.

Why this matters: Norway’s success depends on combining technical leadership with socially intelligible design and port-landscape transformations so rolling out large-scale floating wind is fast, fair and ecologically sensitive.

2) Seychelles — Blue bonds and marine protection

What’s happening now (overview)

In 2018 the Seychelles issued the world’s first sovereign blue bond (backed by a debt swap and development partners) to fund marine conservation, fisheries reform and climate resilience. The instrument blended concessional loans, guarantees and grants to reduce debt burden while directing proceeds into a Blue Grants Fund and Blue Investment Fund for marine management, enforcement, and sustainable economic activities. The approach is widely cited as a prototype for ocean finance and debt-for-nature innovation.

Outcomes & follow-ups

-

The bond financing was used to expand Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), improve fisheries management, and catalyse private investment in sustainable marine enterprises.

-

Analysts view Seychelles as a model but note challenges scaling blue bonds, ensuring transparent monitoring, and finding repeat sovereign issuers. Recent analyses recommend clearer standardization and safeguards for communities.

How design, planning and landscape architecture change the game

Design and landscape disciplines convert finance into legible, locally appropriate projects:

-

Designing resilient coastal investments

-

Blue bond proceeds should require design standards for public works—coastal protection that uses living shorelines, ecologically engineered breakwaters, and community piers that support artisanal fishers rather than displacing them.

-

-

Place-based conservation & public benefit

-

Landscape architects can craft MPA buffer zones that include tourism trails, interpretive centres and small-scale infrastructure that provide alternative livelihoods and educate visitors — increasing public support for protection.

-

-

Monitoring & community co-design

-

Architects and planners design community monitoring stations, low-impact visitor infrastructure, and signage systems that embed local cultural narratives and TEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge) into conservation assets.

-

-

Investment-ready, small-scale blue enterprises

-

Design teams can help incubate small blue enterprises (seaweed processing hubs, reef-based ecotourism platforms) with modular, low-impact facilities that can be financed by blue bonds as measurable social and ecological investments.

-

Example interventions to scale

-

Design brief attached to blue bond project proposals requiring local co-design, cultural interpretation, and nature-based coastal defences.

-

Pilot visitor nodes co-located with MPAs that generate tourism income while protecting reef access and providing interpretive education.

Why this matters: The Seychelles experiment shows that finance instruments can create conservation capital — but design determines whether infrastructure benefits communities and ecosystems or simply produces iconographic PR. Standardizing design-based safeguards increases equity and ecological returns.

3) Portugal — Sustainable aquaculture innovations

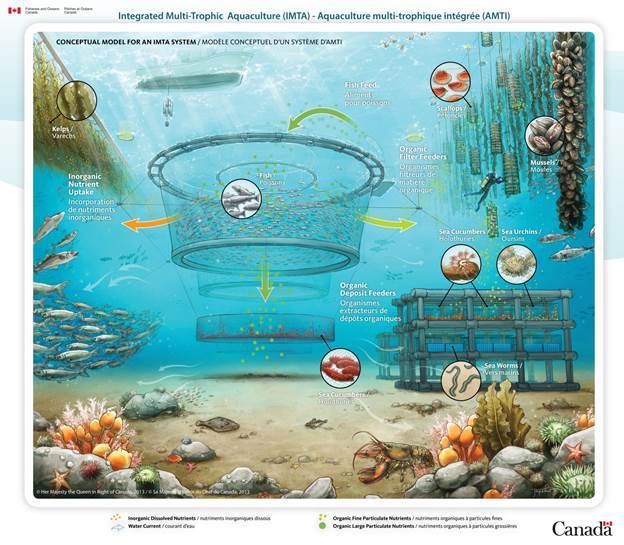

Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture: Over the past decade, scientists have studied ways to improve the productivity and environmental sustainability of marine aquaculture practices. This includes examining the economic and environmental benefits of growing finfish, shellfish and marine plants together – an idea now known as integrated multi-trophic aquaculture. (Source: dfo-mpo.gc.ca)

What’s happening now (overview)

Portugal — and the wider Atlantic-Iberian region — is a hotspot for aquaculture innovation: seaweed (macroalgae) cultivation, shellfish farming, and Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) pilots that combine low-trophic species (seaweed, mussels) with finfish to recycle nutrients and reduce environmental impacts. EU-funded initiatives (e.g., Aquavitae, INNOAQUA, INNOAQUA’s demos) are placing Portugal at the centre of IMTA and seaweed value-chain development.

Technical & market challenges

-

Scaling seaweed aquaculture requires permitting, gear design, processing facilities, and market routes for food, feed, bioplastics and fertilizers.

-

Environmental monitoring and spatial planning are needed to avoid user-conflict (shipping, fisheries, tourism) and ensure ecological carrying capacity.

How design, planning and landscape architecture change the game

Design converts sustainable aquaculture from lab-scale pilot to place-based blue economy:

-

Farm design and gear innovation

-

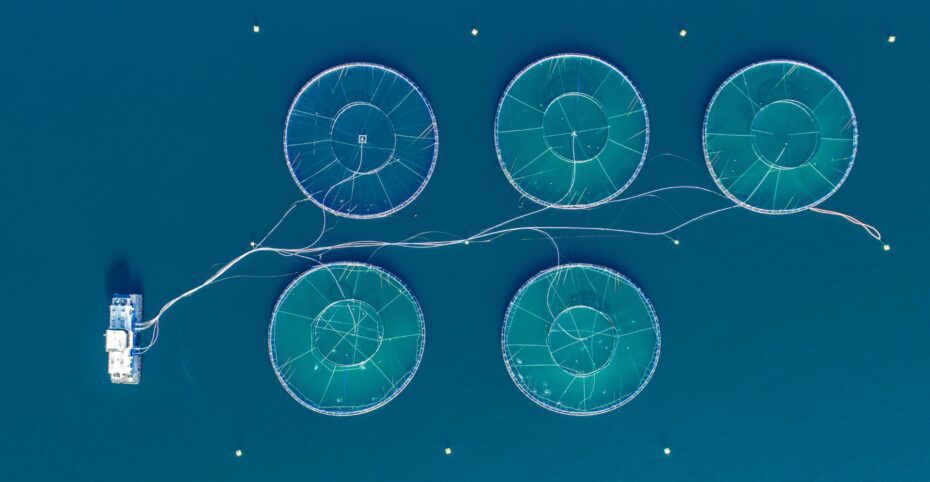

Designers and marine engineers co-create low-visual-impact longline systems, modular cages, and easy-to-recover gear that minimize ghost gear risk and maintain seascape quality.

-

-

Processing & anchor infrastructure

-

Architects design multi-use coastal processing hubs that integrate cold-chains, drying and biomass processing (for alginates, bioplastics) with community training spaces — these hubs can be modular, energy-efficient, and anchored by circular water/energy systems (e.g., solar-drying barns, anaerobic digesters).

-

-

Coastal zoning & IMTA site design

-

Planners use participatory MSP to locate IMTA clusters where currents support nutrient flows and where cumulative impacts are low; landscape architects design shore facilities that combine tourism (trails, educational viewing platforms) with industrial processing in a way that reduces conflicts.

-

-

Product & brand design

-

Designers help create provenance-linked branding (e.g., “Atlantic IMTA”) and packaging solutions that link products to regenerative narratives — crucial for market premiums and consumer buy-in.

-

Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA) (Source: siausa.com)

Example pilots to watch

-

INNOAQUA demos integrating seaweed and finfish in Portuguese waters, testing nutrient uptake, and creating local processing nodes; Aquavitae work on low-trophic species across Atlantic regions. These projects demonstrate how technical aquaculture research must be coupled with design of shore infrastructure and supply chains to be commercially viable.

Why this matters: Portugal’s aquaculture future depends on the design of farm systems, coastal hubs and supply-chain infrastructure. Good place-based design minimizes conflicts, scales production responsibly, and creates visible public benefits (jobs, ecotourism, coastal regeneration).

4) Kenya — Mangrove reforestation and eco-tourism (focus: Gazi Bay, Mida Creek, and beyond)

Beyond restoring mangrove forests, the project seeks to enhance food security through climate-resilient agriculture, improve access to clean water and nutrition, and generate green jobs. (Source: AKF / Christopher Wilton-Steer)

What’s happening now (overview)

Kenya’s mangrove ecosystems (e.g., Gazi Bay, Mida Creek) are internationally recognized for biodiversity and for supporting coastal livelihoods. Recent projects blend restoration, community stewardship and eco-tourism. New restoration plans (Mida Creek 2024–2029) and NGO-led initiatives (Aga Khan Foundation restoration in Gazi Bay) are scaling planting, restoration techniques and community enterprise models. Scientific studies (e.g., modified Riley methods for high-energy sites) inform effective restoration practice.

Threats & barriers

-

Mangrove loss from wood extraction, settlement pressure, and shrimp pond conversion.

-

Restoration failures where hydrology and wave energy aren’t correctly accounted for.

-

Need for sustainable financing that links carbon/sequestration values, tourism revenue and fisheries benefits.

AKF's Gazi Bay project forms part of broader efforts to strengthen climate resilience and support local communities along Kenya's coast. (Source: AKF / Christopher Wilton-Steer)

How design, planning and landscape architecture change the game

Landscape architects and designers act as translators between ecology, community needs and tourism markets:

-

Hydrology-first restoration design

-

Effective restoration begins by re-establishing tidal flow and micro-topography (not just planting). Landscape architects and coastal engineers co-design channels, micro-bunds and wave-break features so seedlings survive. The modified Riley methods and other context-sensitive engineering have improved success rates in Kenya’s high-energy sites.

-

-

Community-oriented eco-tourism infrastructure

-

Design low-impact boardwalks, observation hides, interpretive centres and small guest platforms that generate income for local communities while protecting core restoration zones. Design carefully to avoid mangrove trampling and to maximize visitor education.

-

-

Value-chain design for blue carbon & livelihoods

-

Designers help structure carbon-monitoring interfaces, signage and community dashboards that make blue-carbon payments transparent. They also design small processing facilities (e.g., mangrove honey, eco-certified fish smokehouses, craft centres) that create alternative livelihoods.

-

-

Participatory mapping & cultural design

-

Landscape architects facilitate participatory mapping of sacred groves, nurseries and fishing areas to ensure restoration respects local use rights and cultural values — increasing stewardship and compliance.

-

Example interventions and pilots

-

Mida Creek Restoration Plan (2024–2029): multi-stakeholder plan that includes community governance, restoration techniques, and tourism-oriented design; Aga Khan Foundation’s 226 ha restoration in Gazi Bay focuses on large-scale replanting and hydrological interventions. Local NGOs also develop mangrove boardwalks that support guided ecotours and interpretation centres.

-

Why this matters: Mangrove projects must integrate ecological engineering, local livelihoods, and design for tourism and education — otherwise restoration will fail socially or ecologically. Thoughtful landscape design can make restoration sustainable, resilient and economically viable for coastal communities.

Mangrove restoration in Mida Creek - Kenya(Source: seatrees.org)

Cross-cutting design insights (what designers & landscape architects actually do across these cases)

-

Turn complex data into community-readable design

-

Use GIS/3D visual tools to translate ecological, economic and hazard data into maps, scenarios and visuals for public consultation.

-

-

Design adaptive infrastructure

-

Floating platforms, modular ports, and demountable processing hubs reduce lock-in and encourage reuse and retrofitting.

-

-

Embed cultural values

-

Co-design with local and Indigenous actors to protect cultural seascapes, traditional fisheries and intangible heritage.

-

-

Prototype in living labs

-

Waterfronts and pilot zones serve as demonstration sites (sampling governance, monitoring tech, and visitor experiences) before scaling.

-

-

Make finance accountable through built outcomes

-

Attach design standards and monitoring indicators to blue bonds and similar instruments so that financed projects produce measurable ecological plus social outcomes.

-

Conclusion

These four case studies illustrate powerful, complementary routes toward a just and regenerative blue economy: industrial-scale transitions (Norway), innovative finance (Seychelles), sectoral technological and design innovation (Portugal aquaculture), and people-centred nature restoration (Kenya). Across them, the role of design, planning and landscape architecture is pivotal — not cosmetic but functional and ethical. Designers shape how policy and finance become lived places: ports that don’t kill habitats, bond-funded projects that benefit communities, farms that recycle nutrients and coasts that both protect and generate livelihoods.

If you want, I can:

-

Turn each case study into a standalone blog post with images and pull-quotes.

-

Create a one-page infographic summarizing design actions per case.

-

Provide a downloadable bibliography and links for each cited source.

Featured Posts

Blog Topics

Urban environment & Public spaces

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Waterfront & Coastal Resilience

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Captivating Photography

Stay updated with the latest articles and insights from The Landscape Lab. Here, you will find valuable information and engaging content.

Why Read The Landscape Lab Blog?

The way we design and interact with landscapes is more important than ever. As cities expand, coastlines shift, and climate change reshapes our world, the choices we make about land, water, and urban spaces have lasting impacts. The Landscape Lab Blog is here to spark fresh conversations, challenge conventional thinking, and inspire new approaches to sustainable and resilient design.

If you’re a landscape architect, urban planner, environmentalist, or simply someone who cares about how our surroundings shape our lives, this blog offers insights that matter. We explore the intersections between nature and the built environment, diving into real-world examples of cities adapting to rising sea levels, innovative waterfront designs, and the revival of native ecosystems. We look at how landscapes can work with nature rather than against it, ensuring long-term sustainability and biodiversity.

By reading The Landscape Lab, you'll gain a deeper understanding of the evolving field of landscape design—from rewilding initiatives to regenerative urban planning. Whether it’s uncovering the forgotten history of resilient landscapes, analyzing groundbreaking projects, or discussing the future of green infrastructure, this blog provides a space for learning, inspiration, and meaningful dialogue.

Location:

The Landscape Lab

123 Greenway Drive

Garden City

NY 12345

United Kingdom

Contact Number:

Get in Touch:

contact@thelandscapelab.co.uk

© 2025 thelandscapelab.co.uk - Your go-to blog for landscaping insights