If the Atlantic edge is Lagos’ shield, the lagoon edge is its circulatory system: creeks, wetlands, tidal channels, ferry routes, fisheries, and waterfront neighbourhoods. Lagos State is described as having water bodies and wetlands covering over 40% of its land area, and the coastal zone is characterized by lagoons, creeks, and swamps. This is where flooding becomes amphibious—part tidal, part rainfall, part drainage failure.

What this zone is

The lagoon edge includes Lagos Lagoon and its connected lagoons/creeks—spaces where daily tides interact with stormwater discharge and seasonal rainfall. A major planning implication in Lagos’ own adaptation framing: the lagoons and creeks drain to the sea through a major outlet (the Lagos Lagoon entrance). When that outlet is constrained by tides or surge, water backs up.

The city’s water system mapping (Arup’s City Water Resilience Approach report) lists key lagoons and creeks including Lagos Lagoon, Lekki Lagoon, Ologe Lagoon, Kuramo Waters, Badagry Creek, Five Cowrie Creek, and Port Novo Creeks, and notes that multiple rivers flow into the lagoon system.

What makes it flood-prone

Lagoon-edge flooding often comes from “water meeting water”:

- High tide + heavy rain = stormwater can’t drain → streets and compounds pond.

- Low banks and reclaimed edges = more assets placed at the exact elevation where tides and rainfall collide.

- Eroding, collapsing edges (especially where vegetation was removed).

- Water quality problems: polluted runoff and wastewater reduce ecological resilience and make flooding a public-health crisis.

Theoretical lens: the edge as a gradient, not a wall

A wall is a single elevation with a single failure mode. A living shoreline is a section—subtidal habitat, intertidal plants, high marsh/mangroves, upland buffers—each absorbing energy and storing water at different levels.

NOAA’s living shoreline guidance emphasizes using natural elements (reefs, mangroves/marshes, vegetation) as shoreline stabilization and protection. This is particularly relevant to Lagos because mangrove and wetland ecologies are part of the region’s natural coastal system.

Best-fit design moves for the lagoon edge

1) Living shorelines + mangrove fringe parks

Replace vertical, eroding edges with nature-based revetments: planted terraces, coir rolls, oyster/rock sills, and mangrove belts (where salinity and sediment conditions fit). The goal is wave damping + bank stability + habitat.

2) Tidal parks (public space that expects water level change)

Instead of “fighting the tide,” design parks that choreograph it: boardwalks, inundation terraces, and habitat pockets that become a civic identity.

Global example: Tidal Park Keilehaven, Rotterdam (De Urbanisten) reintroduces a natural estuarine system into an urban setting, creating public space shaped by tidal dynamics.

The Keilehaven Tidal Park in Rotterdam is a pioneering example of how sustainable urban development and rewilding can go hand in hand. The project combines the creation of a city park with the reintroduction of a natural estuarine system in an urban setting_De Urbanisten (Source: landezine.com)

3) “Room for the creeks” (strategic widening + flood storage)

Where channels are constrained, selectively widen and create floodable landscapes that store peak water. This is the lagoon analogue of river floodplain strategy.

Global example: Room for the River Nijmegen (H+N+S Landscape Architects): flood safety is achieved by giving the river more space, while producing a major public river park.

Room for the River, Nijmegen, The Netherlands_H+N+S Landscape Architects (Source: hnsland.nl_Siebe Swart)

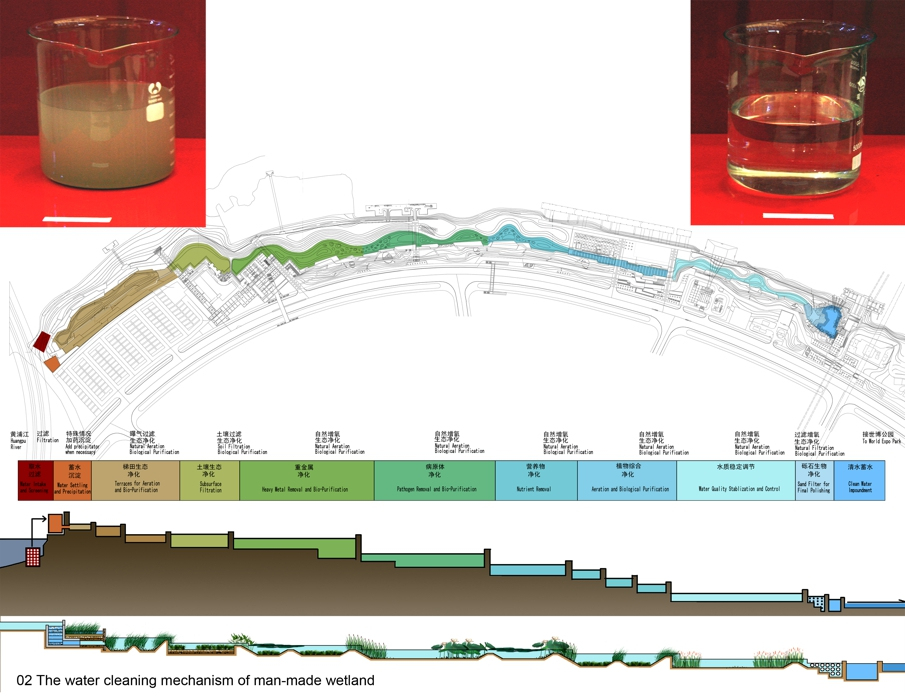

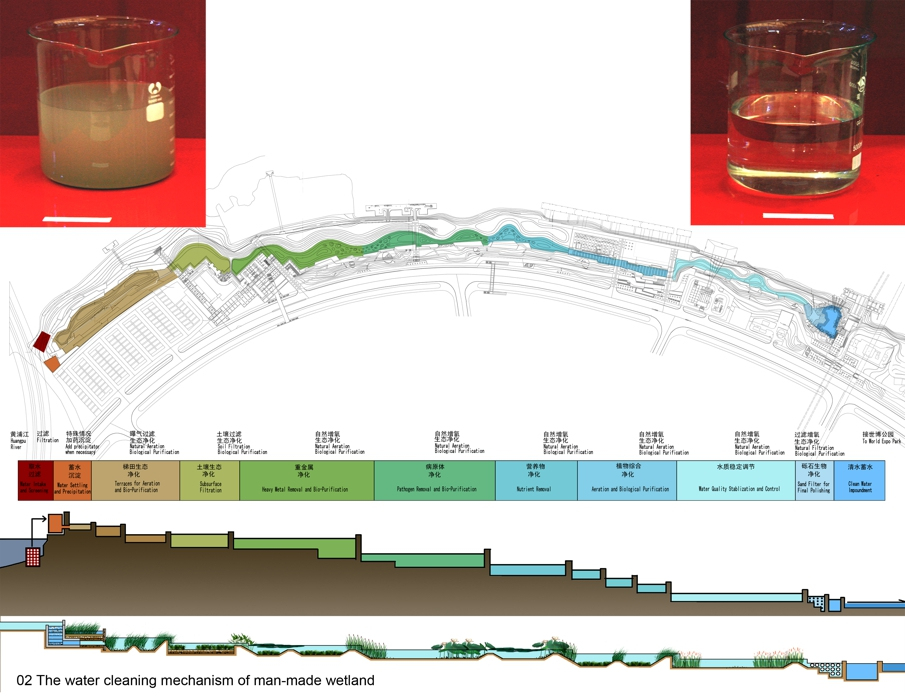

4) Constructed wetlands at the lagoon interface (“treat and slow”)

A lagoon-edge park can also be a water-cleaning machine, filtering runoff before it reaches the lagoon.

Global example: Shanghai Houtan Park (Turenscape) used constructed wetlands and ecological flood control to regenerate a polluted waterfront.

Shanghai Houtan Park, China (Source: turenscape.com). Built on a brownfield of a former industrial site, Houtan Park is a regenerative living landscape

5) Flood-resilient waterfront parks that protect neighbourhoods

Design the shoreline as a soft buffer—wetlands, floodplain planting, and elevated circulation.

Global example: Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park (Weiss/Manfredi + SWA/Balsley) is explicitly designed to accommodate floodwaters and integrates wetlands and an elevated riverwalk as resilience infrastructure.

Hunter’s Point South Waterfront Park transforms 30 acres of post-industrial waterfront into a program-rich public space that simultaneously acts as a protective perimeter for the neighboring residential community. (Source: weissmanfresi.com)

What this could mean on the Lagos lagoon edge

A Lagos lagoon-edge agenda could be organized as a continuous “Lagoon Greenbelt”:

- A protected setback strip where possible (parks, wetlands, mangrove restoration, flood storage).

- A network of tidal parks at key civic points (ferry terminals, bridges, markets).

- Blue corridors that connect inland drainage to lagoon wetlands, so stormwater arrives slowly and cleaner.

- Design standards for lagoon-edge development: raised ground floors, amphibious access routes, floodable courtyards.

The big shift is conceptual: treat the lagoon edge as landscape infrastructure that provides protection, water quality improvement, biodiversity, and mobility—not just “valuable waterfront real estate.”